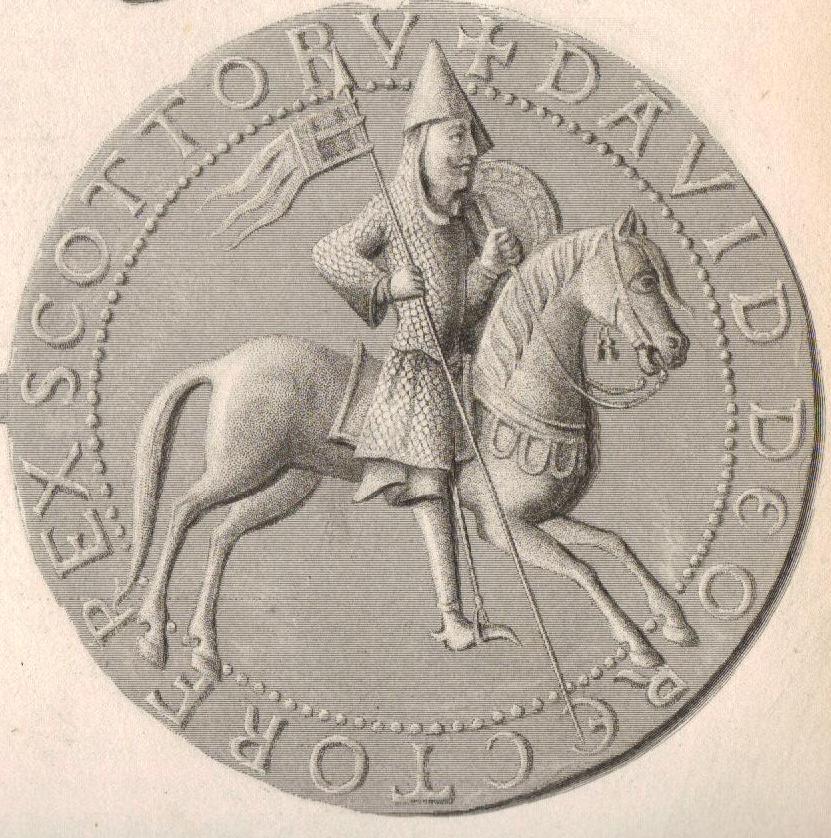

David I or Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim (

Modern

Modern may refer to:

History

* Modern history

** Early Modern period

** Late Modern period

*** 18th century

*** 19th century

*** 20th century

** Contemporary history

* Moderns, a faction of Freemasonry that existed in the 18th century

Phil ...

: ''Daibhidh I mac

haoilChaluim''; – 24 May 1153) was a 12th-century ruler who was

Prince of the Cumbrians

The list of the kings of Strathclyde concerns the kings of Alt Clut, later Strathclyde, a Brythonic kingdom in what is now western Scotland.

The kingdom was ruled from Dumbarton Rock, ''Alt Clut'', the Brythonic name of the rock, until around ...

from 1113 to 1124 and later

King of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiw ...

from 1124 to 1153. The youngest son of

Malcolm III

Malcolm III ( mga, Máel Coluim mac Donnchada, label=Medieval Gaelic; gd, Maol Chaluim mac Dhonnchaidh; died 13 November 1093) was King of Scotland from 1058 to 1093. He was later nicknamed "Canmore" ("ceann mòr", Gaelic, literally "big hea ...

and

Margaret of Wessex

Saint Margaret of Scotland ( gd, Naomh Maighréad; sco, Saunt Marget, ), also known as Margaret of Wessex, was an English princess and a Scottish queen. Margaret was sometimes called "The Pearl of Scotland". Born in the Kingdom of Hungary to th ...

, David spent most of his childhood in

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, but was exiled to

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

temporarily in 1093. Perhaps after 1100, he became a dependent at the court of King

Henry I Henry I may refer to:

876–1366

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry I the Long, Margrave of the ...

. There he was influenced by the Anglo-French culture of the court.

When David's brother

Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon 495–454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Pope Alexander I (died 115), early bishop of Rome

* Pope Alexander I of Alexandria (died 320s), patriarch of ...

died in 1124, David chose, with the backing of Henry I, to take the

Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a la ...

(

Alba

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scottish people, Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed i ...

) for himself. He was forced to engage in warfare against his rival and nephew,

Máel Coluim mac Alaxandair

Máel Coluim mac Alaxandair () was an illegitimate son of Alexander I of Scotland, and was an unsuccessful pretender to the Scottish throne. He is a relatively obscure figure owing primarily to the scarcity of source material, appearing only in pr ...

. Subduing the latter seems to have taken David ten years, a struggle that involved the destruction of

Óengus

In Irish mythology, Aengus or Óengus is one of the Tuatha Dé Danann and probably originally a god associated with youth, love,Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí. ''Myth, Legend & Romance: An encyclopedia of the Irish folk tradition''. Prentice-Hall Press, ...

,

Mormaer of Moray

The title Earl of Moray, Mormaer of Moray or King of Moray was originally held by the rulers of the Province of Moray, which existed from the 10th century with varying degrees of independence from the Kingdom of Alba to the south. Until 1130 th ...

. David's victory allowed expansion of control over more distant regions theoretically part of his Kingdom. After the death of his former patron Henry I, David supported the claims of Henry's daughter and his own niece,

Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda ( 7 February 110210 September 1167), also known as the Empress Maude, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter of King Henry I of England, she moved to Germany as ...

, to the throne of England. In the process, he came into conflict with King

Stephen

Stephen or Steven is a common English first name. It is particularly significant to Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; ...

and was able to expand his power in northern England, despite his defeat at the

Battle of the Standard in 1138. David I is a

saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Š, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

of the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, with his

feast day celebrated on 24 May.

The term "

Davidian Revolution

The Davidian Revolution is a name given by many scholars to the changes which took place in the Kingdom of Scotland during the reign of David I (1124–1153). These included his foundation of burghs, implementation of the ideals of Gregorian ...

" is used by many scholars to summarise the changes that took place in Scotland during his reign. These included his foundation of

burgh

A burgh is an autonomous municipal corporation in Scotland and Northern England, usually a city, town, or toun in Scots. This type of administrative division existed from the 12th century, when King David I created the first royal burghs. Burg ...

s and regional markets, implementation of the ideals of

Gregorian Reform

The Gregorian Reforms were a series of reforms initiated by Pope Gregory VII and the circle he formed in the papal curia, c. 1050–80, which dealt with the moral integrity and independence of the clergy. The reforms are considered to be na ...

, foundation of

monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

, Normanisation of the Scottish government, and the introduction of

feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

through immigrant

French and

Anglo-French

Anglo-French (or sometimes Franco-British) may refer to:

*France–United Kingdom relations

*Anglo-Norman language or its decendants, varieties of French used in medieval England

*Anglo-Français and Français (hound), an ancient type of hunting d ...

knights.

Early years

David was born on a date unknown in 1084 in Scotland. He was probably the eighth son of

King Malcolm III

Malcolm III ( mga, Máel Coluim mac Donnchada, label=Medieval Gaelic; gd, Maol Chaluim mac Dhonnchaidh; died 13 November 1093) was King of Scotland from 1058 to 1093. He was later nicknamed "Canmore" ("ceann mòr", Scottish Gaelic, Gaelic, lit ...

, and certainly the sixth and youngest borne by Malcolm's second wife,

Margaret of Wessex

Saint Margaret of Scotland ( gd, Naomh Maighréad; sco, Saunt Marget, ), also known as Margaret of Wessex, was an English princess and a Scottish queen. Margaret was sometimes called "The Pearl of Scotland". Born in the Kingdom of Hungary to th ...

. He was the grandson of

King Duncan I

Donnchad mac Crinain ( gd, Donnchadh mac Crìonain; anglicised as Duncan I, and nicknamed An t-Ilgarach, "the Diseased" or "the Sick"; c. 1001 – 14 August 1040)Broun, "Duncan I (d. 1040)". was king of Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland (''Kingdom ...

.

In 1093, King Malcolm and David's brother Edward were killed at the

River Aln

The River Aln () runs through the county of Northumberland in England. It rises in Alnham in the Cheviot Hills and discharges into the North Sea at Alnmouth on the east coast of England.

The river gives its name to the town of Alnwick and t ...

during an invasion of

Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land on ...

. David and his two brothers

Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

and

Edgar were probably present when their mother died shortly afterwards. According to later medieval tradition, the three brothers were in

Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

when they were besieged by their paternal uncle

Donald III

Donald III (Medieval Gaelic: Domnall mac Donnchada; Modern Gaelic: ''Dòmhnall mac Dhonnchaidh''), and nicknamed "Donald the Fair" or "Donald the White" (Medieval Gaelic:"Domnall Bán", anglicised as Donald Bane/Bain or Donalbane/Donalbain) (c. ...

, who made himself king. It is not certain what happened next, but an insertion in the ''

Chronicle of Melrose

The ''Chronicle of Melrose'' is a medieval chronicle from the Cottonian Manuscript, Faustina B. ix within the British Museum. It was written by unknown authors, though evidence in the writing shows that it most likely was written by the monks a ...

'' states that Donald forced his three nephews into exile, although he was allied with another of his nephews,

Edmund

Edmund is a masculine given name or surname in the English language. The name is derived from the Old English elements ''ēad'', meaning "prosperity" or "riches", and ''mund'', meaning "protector".

Persons named Edmund include:

People Kings and ...

. John of Fordun wrote, centuries later, that an escort into England was arranged for them by their maternal uncle

Edgar Ætheling

Edgar Ætheling or Edgar II (c. 1052 – 1125 or after) was the last male member of the royal house of Cerdic of Wessex. He was elected King of England by the Witenagemot in 1066, but never crowned.

Family and early life

Edgar was born ...

.

King

William Rufus

William II ( xno, Williame; – 2 August 1100) was King of England from 26 September 1087 until his death in 1100, with powers over Normandy and influence in Scotland. He was less successful in extending control into Wales. The third so ...

of England opposed Donald's accession to the northerly kingdom. He sent the eldest son of Malcolm, David's half-brother

Duncan, into Scotland with an army. Duncan was killed within the year, and so in 1097 William sent Duncan's half-brother Edgar into Scotland. The latter was more successful, and was crowned by the end of 1097.

During the power struggle of 1093–97, David was in England. In 1093, he may have been about nine years old. From 1093 until 1103 David's presence cannot be accounted for in detail, but he appears to have been in Scotland for the remainder of the 1090s. When William Rufus was killed, his brother

Henry Beauclerc

Henry I (c. 1068 – 1 December 1135), also known as Henry Beauclerc, was King of England from 1100 to his death in 1135. He was the fourth son of William the Conqueror and was educated in Latin and the liberal arts. On William's death in ...

seized power and married David's sister,

Matilda

Matilda or Mathilda may refer to:

Animals

* Matilda (chicken) (1990–2006), World's Oldest Living Chicken record holder

* Matilda (horse) (1824–1846), British Thoroughbred racehorse

* Matilda, a dog of the professional wrestling tag-team The ...

. The marriage made David the brother-in-law of the ruler of England. From that point onwards, David was probably an important figure at the English court. Despite his Gaelic background, by the end of his stay in England, David had become a fully Normanised prince.

William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury ( la, Willelmus Malmesbiriensis; ) was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. He has been ranked among the most talented English historians since Bede. Modern historian C. Warren Hollister described him as "a ...

wrote that it was in this period that David "rubbed off all tarnish of Scottish barbarity through being polished by intercourse and friendship with us".

Early rule 1113–1124

Prince of the Cumbrians

David's brother King Edgar had visited William Rufus in May 1099 and bequeathed to David extensive territory to the south of the

river Forth

The River Forth is a major river in central Scotland, long, which drains into the North Sea on the east coast of the country. Its drainage basin covers much of Stirlingshire in Scotland's Central Belt. The Gaelic name for the upper reach of th ...

. On 8 January 1107, Edgar died. His younger brother Alexander took the throne. It has been assumed that David took control of his

inheritance

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, Title (property), titles, debts, entitlements, Privilege (law), privileges, rights, and Law of obligations, obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ ...

– the southern lands bequeathed by Edgar – soon after the latter's death. However, it cannot be shown that he possessed his inheritance until his foundation of

Selkirk Abbey

Kelso Abbey is a ruined Scottish abbeys, Scottish abbey in Kelso, Scottish Borders, Kelso, Scotland. It was founded in the 12th century by a community of Tironensian monks first brought to Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland in the reign of Alexander ...

late in 1113. According to

Richard Oram

Professor Richard D. Oram F.S.A. (Scot.) is a Scottish historian. He is a professor of medieval and environmental history at the University of Stirling and an honorary lecturer in history at the University of Aberdeen. He is also the director of ...

, it was only in 1113, when Henry returned to England from Normandy, that David was at last in a position to claim his inheritance in southern Scotland.

King Henry's backing seems to have been enough to force King Alexander to recognise his younger brother's claims. This probably occurred without bloodshed, but through threat of force nonetheless. David's aggression seems to have inspired resentment amongst some native Scots. A

Middle Gaelic

Middle Irish, sometimes called Middle Gaelic ( ga, An Mheán-Ghaeilge, gd, Meadhan-Ghàidhlig), is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from AD; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old Engli ...

quatrain from this period complains that:

If "divided from" is anything to go by, this quatrain may have been written in David's new territories in southern Scotland. The lands in question consisted of the

pre-1975 counties

The shires of Scotland ( gd, Siorrachdan na h-Alba), or counties of Scotland, are historic subdivisions of Scotland established in the Middle Ages and used as administrative divisions until 1975. Originally established for judicial purposes (bei ...

of

Roxburghshire,

Selkirkshire

Selkirkshire or the County of Selkirk ( gd, Siorrachd Shalcraig) is a historic county and registration county of Scotland. It borders Peeblesshire to the west, Midlothian to the north, Roxburghshire to the east, and Dumfriesshire to the south. ...

,

Berwickshire

Berwickshire ( gd, Siorrachd Bhearaig) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area in south-eastern Scotland, on the English border. Berwickshire County Council existed from 1890 until 1975, when the area became part of t ...

,

Peeblesshire

Peeblesshire ( gd, Siorrachd nam Pùballan), the County of Peebles or Tweeddale is a historic county of Scotland. Its county town is Peebles, and it borders Midlothian to the north, Selkirkshire to the east, Dumfriesshire to the south, and Lan ...

and

Lanarkshire

Lanarkshire, also called the County of Lanark ( gd, Siorrachd Lannraig; sco, Lanrikshire), is a historic county, lieutenancy area and registration county in the central Lowlands of Scotland.

Lanarkshire is the most populous county in Scotlan ...

. David, moreover, gained the title , "

Prince of the Cumbrians

The list of the kings of Strathclyde concerns the kings of Alt Clut, later Strathclyde, a Brythonic kingdom in what is now western Scotland.

The kingdom was ruled from Dumbarton Rock, ''Alt Clut'', the Brythonic name of the rock, until around ...

", as attested in David's charters from this era. Although this was a large slice of Scotland south of the river Forth, the region of Galloway-proper was entirely outside David's control. David may perhaps have had varying degrees of overlordship in parts of

Dumfriesshire

Dumfriesshire or the County of Dumfries or Shire of Dumfries (''Siorrachd Dhùn Phris'' in Gaelic) is a historic county and registration county in southern Scotland. The Dumfries lieutenancy area covers a similar area to the historic county.

I ...

,

Ayrshire

Ayrshire ( gd, Siorrachd Inbhir Àir, ) is a historic county and registration county in south-west Scotland, located on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. Its principal towns include Ayr, Kilmarnock and Irvine and it borders the counties of Re ...

,

Dunbartonshire

Dunbartonshire ( gd, Siorrachd Dhùn Breatann) or the County of Dumbarton is a historic county, lieutenancy area and registration county in the west central Lowlands of Scotland lying to the north of the River Clyde. Dunbartonshire borders P ...

and

Renfrewshire

Renfrewshire () ( sco, Renfrewshire; gd, Siorrachd Rinn Friù) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.

Located in the west central Lowlands, it is one of three council areas contained within the boundaries of the historic county of Renfr ...

. In the lands between Galloway and the Principality of Cumbria, David eventually set up large-scale marcher lordships, such as

Annandale for

Robert de Brus

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (Scottish Gaelic: ''Raibeart an Bruis''), was King of Scots from 1306 to his death in 1329. One of the most renowned warriors of his generation, Robert eventuall ...

,

Cunningham

Cunningham is a surname of Scottish origin, see Clan Cunningham.

Notable people sharing this surname

A–C

* Aaron Cunningham (born 1986), American baseball player

*Abe Cunningham, American drummer

* Adrian Cunningham (born 1960), Australian ...

for

Hugh de Morville, and possibly

Strathgryfe for

Walter Fitzalan

Walter FitzAlan (1177) was a twelfth-century English baron who became a Scottish magnate and Steward of Scotland. He was a younger son of Alan fitz Flaad and Avelina de Hesdin. In about 1136, Walter entered into the service of David I, King o ...

.

Earl of Huntingdon

In the later part of 1113, King Henry gave David the hand of Matilda of Huntingdon, daughter and heiress of

Waltheof, Earl of Northumberland. The marriage brought with it the "Honour of Huntingdon", a lordship scattered through the shires of

Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England; ...

,

Huntingdon

Huntingdon is a market town in the Huntingdonshire district in Cambridgeshire, England. The town was given its town charter by King John in 1205. It was the county town of the historic county of Huntingdonshire. Oliver Cromwell was born there ...

, and

Bedford

Bedford is a market town in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 Census, the population of the Bedford built-up area (including Biddenham and Kempston) was 106,940, making it the second-largest settlement in Bedfordshire, behind Luton, whilst ...

. Within a few years, Matilda bore a son, whom David named

Henry

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

after his patron.

The new territories which David controlled were a valuable supplement to his income and manpower, increasing his status as one of the most powerful magnates in the Kingdom of the English. Moreover, Matilda's father Waltheof had been

Earl of Northumberland

The title of Earl of Northumberland has been created several times in the Peerage of England and of Great Britain, succeeding the title Earl of Northumbria. Its most famous holders are the House of Percy (''alias'' Perci), who were the most po ...

, a defunct lordship which had covered the far north of England and included

Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

and

Westmorland

Westmorland (, formerly also spelt ''Westmoreland'';R. Wilkinson The British Isles, Sheet The British IslesVision of Britain/ref> is a historic county in North West England spanning the southern Lake District and the northern Dales. It had an ...

,

Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land on ...

-proper, as well as overlordship of the bishopric of Durham. After King Henry's death, David revived the claim to this earldom for his son,

Henry

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

.

David's activities and whereabouts after 1114 are not always easy to trace. He spent much of his time outside his principality, in England and in Normandy. Despite the death of his sister on 1 May 1118, David still possessed the favour of King Henry when his brother Alexander died in 1124, leaving Scotland without a king.

Political and military events in Scotland during David's kingship

In spite of the fact that King David spent his childhood in Scotland, Michael Lynch and Richard Oram portray David as having little initial connection with the culture and society of the Scots; but both likewise argue that David became increasingly re-Gaelicised in the later stages of his reign. Whatever the case, David's claim to be heir to the Scottish kingdom was doubtful. However, the Scots never followed the Norman laws of primogeniture. David was the youngest of eight sons of the fifth from last king. Two more recent kings had produced sons,

William fitz Duncan

William fitz Duncan (a modern anglicisation of the Old French Guillaume fils de Duncan and the Middle Irish Uilleam mac Donnchada) was a Scottish prince, the son of King Duncan II of Scotland by his wife Ethelreda of Dunbar. He was a territoria ...

, son of King Donnchad II, and

Máel Coluim, son of the last king Alexander, but since Scots had never adopted the rules of

primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

that was not a barrier to his kingship, and unlike David, neither William nor Máel Coluim had the support of Henry. So when Alexander died in 1124, the aristocracy of Scotland could either accept David as king, or face war with both David and Henry I.

Coronation and struggle for the kingdom

Alexander's son, Máel Coluim, chose war.

Orderic Vitalis reported that Máel Coluim mac Alaxandair "affected to snatch the kingdom from

avid and fought against him two sufficiently fierce battles; but David, who was loftier in understanding and in power and wealth, conquered him and his followers". Máel Coluim escaped unharmed into areas of Scotland not yet under David's control, and in those areas gained shelter and aid.

In either April or May of the same year, David was crowned King of Scotland ( sga,

rí

Rí, or commonly ríg ( genitive), is an ancient Gaelic word meaning 'king'. It is used in historical texts referring to the Irish and Scottish kings, and those of similar rank. While the Modern Irish word is exactly the same, in modern Scottis ...

(gh) Alban;

Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. In this region it served as the primary written language, though local languages were also written to varying degrees. Latin functioned ...

: ) at

Scone

A scone is a baked good, usually made of either wheat or oatmeal with baking powder as a leavening agent, and baked on sheet pans. A scone is often slightly sweetened and occasionally glazed with egg wash. The scone is a basic component ...

. If later Scottish and Irish evidence can be taken as evidence, the ceremony of coronation was a series of elaborate traditional rituals, of the kind infamous in the Anglo-French world of the 12th century for their "unchristian" elements.

Ailred of Rievaulx, friend and one-time member of David's court, reported that David "so abhorred those acts of homage which are offered by the Scottish nation in the manner of their fathers upon the recent promotion of their kings, that he was with difficulty compelled by the bishops to receive them".

Outside his Cumbrian principality and the southern fringe of Scotland-proper, David exercised little power in the 1120s, and in the words of Richard Oram, was "king of Scots in little more than name". He was probably in that part of Scotland he did rule for most of the time between late 1127 and 1130.

[Oram, ''David'', p. 83.] However, he was at the court of Henry in 1126 and in early 1127, and returned to Henry's court in 1130, serving as a judge at

Woodstock

Woodstock Music and Art Fair, commonly referred to as Woodstock, was a music festival held during August 15–18, 1969, on Max Yasgur's dairy farm in Bethel, New York, United States, southwest of the town of Woodstock. Billed as "an Aq ...

for the

treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

trial of

Geoffrey de Clinton

Geoffrey de Clinton (died c. 1134) was an Anglo-Norman noble, chamberlain and treasurer to King Henry I of England. He was foremost amongst the men king Henry "raised from the dust". He married Lescelina.

Life

Clinton's family origins are a litt ...

.

It was in this year that David's wife, Matilda of Huntingdon, died. Possibly as a result of this, and while David was still in southern England,

Scotland-proper rose up in arms against him. The instigator was, again, his nephew Máel Coluim, who now had the support of

Óengus of Moray

Óengus of Moray (''Oenghus mac inghine Lulaich, ri Moréb'') was the last king of Moray of the native line, ruling Moray in what is now northeastern Scotland from an unknown date until his death in 1130.

Óengus is known to have been the son of ...

. King Óengus was David's most powerful vassal, a man who, as grandson of King

Lulach of Scotland

Lulach mac Gille Coemgáin ( Modern Gaelic: ''Lughlagh mac Gille Chomghain'', known in English simply as Lulach, and nicknamed Tairbith, "the Unfortunate" and Fatuus, "the Simple-minded" or "the Foolish"; before 1033 – 17 March 1058) was King of ...

, even had his own claim to the kingdom. The rebel Scots had advanced into

Angus

Angus may refer to:

Media

* ''Angus'' (film), a 1995 film

* ''Angus Og'' (comics), in the ''Daily Record''

Places Australia

* Angus, New South Wales

Canada

* Angus, Ontario, a community in Essa, Ontario

* East Angus, Quebec

Scotland

* An ...

, where they were met by David's

Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527–879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527–918

, era=Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, ye ...

n

constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in criminal law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. A constable is commonly the rank of an officer within the police. Other peop ...

,

Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

; a battle took place at

Stracathro near

Brechin

Brechin (; gd, Breichin) is a city and former Royal burgh in Angus, Scotland. Traditionally Brechin was described as a city because of its cathedral and its status as the seat of a pre-Reformation Roman Catholic diocese (which continues today ...

. According to the ''

Annals of Ulster

The ''Annals of Ulster'' ( ga, Annála Uladh) are annals of medieval Ireland. The entries span the years from 431 AD to 1540 AD. The entries up to 1489 AD were compiled in the late 15th century by the scribe Ruaidhrí Ó Luinín, ...

'', 1000 of Edward's army, and 4000 of Óengus' army – including Óengus himself – died.

According to Orderic Vitalis, Edward followed up the killing of Óengus by marching north into Moray itself, which, in Orderic's words, "lacked a defender and lord"; and so Edward, "with God's help obtained the entire duchy of that extensive district". However, this was far from the end of it. Máel Coluim escaped, and four years of continuing civil war followed; for David this period was quite simply a "struggle for survival".

It appears that David asked for and obtained extensive military aid from King Henry. Ailred of Rievaulx related that at this point a large fleet and a large army of Norman knights, including Walter l'Espec, were sent by Henry to Carlisle in order to assist David's attempt to root out his Scottish enemies. The fleet seems to have been used in the

Irish Sea

The Irish Sea or , gv, Y Keayn Yernagh, sco, Erse Sie, gd, Muir Èireann , Ulster-Scots: ''Airish Sea'', cy, Môr Iwerddon . is an extensive body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Ce ...

, the

Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde is the mouth of the River Clyde. It is located on the west coast of Scotland and constitutes the deepest coastal waters in the British Isles (it is 164 metres deep at its deepest). The firth is sheltered from the Atlantic ...

and the entire

Argyll

Argyll (; archaically Argyle, in modern Gaelic, ), sometimes called Argyllshire, is a historic county and registration county of western Scotland.

Argyll is of ancient origin, and corresponds to most of the part of the ancient kingdom of ...

coast, where Máel Coluim was probably at large among supporters. In 1134, Máel Coluim was captured and imprisoned in

Roxburgh Castle

Roxburgh Castle is a ruined royal castle that overlooks the junction of the rivers Tweed and Teviot, in the Borders region of Scotland. The town and castle developed into the royal burgh of Roxburgh, which the Scots destroyed along with the ca ...

. Since modern historians no longer confuse him with "

Malcolm MacHeth", it is clear that nothing more is ever heard of Máel Coluim mac Alaxandair, except perhaps that his sons were later allied with

Somerled

Somerled (died 1164), known in Middle Irish as Somairle, Somhairle, and Somhairlidh, and in Old Norse as Sumarliði , was a mid-12th-century Norse-Gaelic lord who, through marital alliance and military conquest, rose in prominence to create the ...

.

Pacification of the west and north

Richard Oram puts forward the suggestion that it was during this period that David granted Walter fitz Alan

Strathgryfe, with northern

Kyle

Kyle or Kyles may refer to:

Places

Canada

* Kyle, Saskatchewan, Canada

Ireland

* Kyle, County Laois

* Kyle, County Wexford

Scotland

* Kyle, Ayrshire, area of Scotland which stretched across parts of modern-day East Ayrshire and South Ayrshir ...

and the area around

Renfrew, forming what would become the "Stewart" lordship of Strathgryfe; he also suggests that Hugh de Morville may have gained

Cunningham

Cunningham is a surname of Scottish origin, see Clan Cunningham.

Notable people sharing this surname

A–C

* Aaron Cunningham (born 1986), American baseball player

*Abe Cunningham, American drummer

* Adrian Cunningham (born 1960), Australian ...

and the settlement of "Strathyrewen" (i.e.

Irvine). This would indicate that the 1130–34 campaign had resulted in the acquisition of these territories.

How long it took to pacify Moray is not known, but in this period David appointed his nephew William fitz Duncan to succeed Óengus, perhaps in compensation for the exclusion from the succession to the Scottish throne caused by the coming of age of David's son

Henry

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

. William may have been given the daughter of Óengus in marriage, cementing his authority in the region. The burghs of

Elgin and

Forres

Forres (; gd, Farrais) is a town and former royal burgh in the north of Scotland on the Moray coast, approximately northeast of Inverness and west of Elgin. Forres has been a winner of the Scotland in Bloom award on several occasions. There ...

may have been founded at this point, consolidating royal authority in Moray. David also founded

Urquhart Priory

Urquhart Priory was a Benedictine monastic community in Moray; the priory was dedicated to the Holy Trinity. It was founded by King David I of Scotland in 1136 as a cell of Dunfermline Abbey in the aftermath of the defeat of King Óengus of Moray. ...

, possibly as a "victory monastery", and assigned to it a percentage of his ''

cain

Cain ''Káïn''; ar, قابيل/قايين, Qābīl/Qāyīn is a Biblical figure in the Book of Genesis within Abrahamic religions. He is the elder brother of Abel, and the firstborn son of Adam and Eve, the first couple within the Bible. He wa ...

'' (tribute) from Argyll.

During this period too, a marriage was arranged between the son of

Matad, Mormaer of Atholl

Matad of Atholl was Mormaer of Atholl, 1130s–1153/59.

It is possible that he was granted the Mormaerdom by a King of Scotland, as suggested by Roberts, rather than merely inheriting it. However, this is unlikely. If he did inherit it, he i ...

, and the daughter of

Haakon Paulsson

Haakon may refer to:

Given names

* Haakon (given name)

* Håkon, modern Norwegian spelling of the name

* Håkan, Swedish spelling of the name

* Hakon, Danish spelling of the name

People

Norwegian royalty

* Haakon I of Norway (c. 920–961), ...

,

Earl of Orkney

Earl of Orkney, historically Jarl of Orkney, is a title of nobility encompassing the archipelagoes of Orkney and Shetland, which comprise the Northern Isles of Scotland. Originally founded by Norse invaders, the status of the rulers of the Nort ...

. The marriage temporarily secured the northern frontier of the Kingdom, and held out the prospect that a son of one of David's

mormaer

In early Middle Ages, medieval Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, a mormaer was the Scottish Gaelic, Gaelic name for a regional or provincial ruler, theoretically second only to the Kings of Scots, King of Scots, and the senior of a ''Toísech'' (chi ...

s could gain

Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

and

Caithness

Caithness ( gd, Gallaibh ; sco, Caitnes; non, Katanes) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland.

Caithness has a land boundary with the historic county of Sutherland to the west and is otherwise bounded by ...

for the Kingdom of Scotland. Thus, by the time Henry I died on 1 December 1135, David had more of Scotland under his control than ever before.

Dominating the north

While fighting

King Stephen and attempting to dominate northern England in the years following 1136, David was continuing his drive for control of the far north of Scotland. In 1139, his cousin, the five-year-old

Harald Maddadsson

Harald Maddadsson (Old Norse: ''Haraldr Maddaðarson'', Gaelic: ''Aralt mac Mataid'') (c. 1134 – 1206) was Earl of Orkney and Mormaer of Caithness from 1139 until 1206. He was the son of Matad, Mormaer of Atholl, and Margaret, daughter ...

, was given the title of "Earl" and half the lands of the

earldom of Orkney

The Earldom of Orkney is the official status of the Orkney Islands. It was originally a Norse feudal dignity in Scotland which had its origins from the Viking period. In the ninth and tenth centuries it covered more than the Northern Isles (' ...

, in addition to Scottish Caithness. Throughout the 1140s Caithness and Sutherland were brought back under the Scottish zone of control. Sometime before 1146 David appointed a native Scot called

Aindréas to be the first

Bishop of Caithness

The Bishop of Caithness was the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of Caithness, one of Scotland's 13 medieval bishoprics. The first referenced bishop of Caithness was Aindréas, a Gael who appears in sources between 1146 and 1151 as bishop. Ai ...

, a bishopric which was based at

Halkirk

Halkirk ( gd, Hàcraig) is a village on the River Thurso in Caithness, in the Highland council area of Scotland. From Halkirk the B874 road runs towards Thurso in the north and towards Georgemas in the east. The village is within the parish o ...

, near

Thurso

Thurso (pronounced ; sco, Thursa, gd, Inbhir Theòrsa ) is a town and former burgh on the north coast of the Highland council area of Scotland. Situated in the historical County of Caithness, it is the northernmost town on the island of Gre ...

, in an area which was ethnically Scandinavian.

In 1150, it looked like Caithness and the whole earldom of Orkney were going to come under permanent Scottish control. However, David's plans for the north soon began to encounter problems. In 1151, King

Eystein II of Norway

Eystein II (Old Norse: ''Eysteinn Haraldsson'', Norwegian: ''Øystein Haraldsson''); c.1125 – 21 August 1157) was king of Norway from 1142 to 1157. He ruled as co-ruler with his brothers, Inge Haraldsson and Sigurd Munn. He was killed in ...

put a spanner in the works by sailing through the waterways of Orkney with a large fleet and catching the young Harald unaware in his residence at Thurso. Eystein forced Harald to pay

fealty

An oath of fealty, from the Latin ''fidelitas'' (faithfulness), is a pledge of allegiance of one person to another.

Definition

In medieval Europe, the swearing of fealty took the form of an oath made by a vassal, or subordinate, to his lord. "Fea ...

as a condition of his release. Later in the year David hastily responded by supporting the claims to the Orkney earldom of Harald's rival

Erlend Haraldsson

Erlend Haraldsson (c.1124 – 21 December 1154) was joint Earl of Orkney from 1151 to 1154. The son of Earl Harald Haakonsson,Thomson (2008) p. 89 he ruled with Harald Maddadsson and Rögnvald Kali Kolsson.Thomson (2008) p. 101

This was a tur ...

, granting him half of Caithness in opposition to Harald. King Eystein responded in turn by making a similar grant to this same Erlend, cancelling the effect of David's grant. David's weakness in Orkney was that the Norwegian kings were not prepared to stand back and let him reduce their power.

England

David's relationship with England and the English crown in these years is usually interpreted in two ways. Firstly, his actions are understood in relation to his connections with the King of England. No historian is likely to deny that David's early career was largely manufactured by King Henry I of England. David was the latter's brother-in-law and "greatest protégé", one of Henry's "new men". His hostility to Stephen can be interpreted as an effort to uphold the intended inheritance of Henry I, the succession of his daughter and David's niece

Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda ( 7 February 110210 September 1167), also known as the Empress Maude, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter of King Henry I of England, she moved to Germany as ...

. David carried out his wars in her name, joined her when she arrived in England, and later knighted her son

Henry

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

.

However, David's policy towards England can be interpreted in an additional way. David was the independence-loving king trying to build a "Scoto-Northumbrian" realm by seizing the most northerly parts of the English kingdom. In this perspective, David's support for Matilda is used as a pretext for land-grabbing. David's maternal descent from the

House of Wessex

The House of Wessex, also known as the Cerdicings and the West Saxon dynasty, refers to the family, traditionally founded by Cerdic of Wessex, Cerdic, that ruled Wessex in Southern England from the early 6th century. The house became dominant in so ...

and his son Henry's maternal descent from the English earls of Northumberland is thought to have further encouraged such a project, a project which came to an end only after Henry II ordered David's child successor

Máel Coluim IV

Malcolm IV ( mga, Máel Coluim mac Eanric, label=Medieval Gaelic; gd, Maol Chaluim mac Eanraig), nicknamed Virgo, "the Maiden" (between 23 April and 24 May 11419 December 1165) was King of Scotland from 1153 until his death. He was the eldest ...

to hand over the most important of David's gains. It is clear that neither one of these interpretations can be taken without some weight being given to the other.

Usurpation of Stephen and First Treaty of Durham

Henry I had arranged his inheritance to pass to his daughter

Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda ( 7 February 110210 September 1167), also known as the Empress Maude, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter of King Henry I of England, she moved to Germany as ...

. Instead,

Stephen

Stephen or Steven is a common English first name. It is particularly significant to Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; ...

, younger brother of

Theobald II, Count of Blois, seized the throne. David had been the first lay person to take the oath to uphold the succession of Matilda in 1127, and when Stephen was crowned on 22 December 1135, David decided to make war.

Before December was over, David marched into northern England, and by the end of January he had occupied the castles of

Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern England, Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers River Eden, Cumbria, Eden, River C ...

,

Wark

Wark or WARK may refer to:

*Wark (surname), including a list of people with the surname

*Wark (river), a river in Luxembourg

*WARK (AM), talk radio station in Hagerstown, Maryland

*Wark on Tweed, a village in Carham parish, in the north of Englan ...

,

Alnwick

Alnwick ( ) is a market town in Northumberland, England, of which it is the traditional county town. The population at the 2011 Census was 8,116.

The town is on the south bank of the River Aln, south of Berwick-upon-Tweed and the Scottish bor ...

,

Norham

Norham ( ) is a village and civil parish in Northumberland, England, It is located south-west of Berwick on the south side of the River Tweed where it is the border with Scotland.

History

Its ancient name was Ubbanford. Ecgred of Lindisfarne ...

and

Newcastle Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area in Australia, named after Newcastle ...

. By February David was at Durham, but an army led by King Stephen met him there. Rather than fight a pitched battle, a treaty was agreed whereby David would retain Carlisle, while David's son Henry was re-granted the title and half the lands of the earldom of Huntingdon, territory which had been confiscated during David's revolt. On Stephen's side he received back the other castles; and while David would do no homage, Stephen was to receive the homage of Henry for both Carlisle and the other English territories. Stephen also gave the rather worthless but for David face-saving promise that if he ever chose to resurrect the defunct earldom of Northumberland, Henry would be given first consideration. Importantly, the issue of Matilda was not mentioned. However, the first Durham treaty quickly broke down after David took insult at the treatment of his son Henry at Stephen's court.

Renewal of war and Clitheroe

When the winter of 1136–37 was over, David prepared again to invade England. The King of the Scots massed an army on Northumberland's border, to which the English responded by gathering an army at Newcastle.

[ David Crouch, ''The Reign of King Stephen, 1135–1154'', Ed. Longman, 2000, p. 70.] Once more pitched battle was avoided, and instead a truce was agreed until December.

When December fell, David demanded that Stephen hand over the whole of the old earldom of Northumberland. Stephen's refusal led to David's third invasion, this time in January 1138.

The army which invaded England in January and February 1138 shocked the English chroniclers.

Richard of Hexham

Richard of Hexham (fl. 1141) was an English chronicler. He became prior of Hexham about 1141, and died between 1155 and 1167.

He wrote ''Brevis Annotatio'', a short history of the church of Hexham from 674 to 1138, for which he borrowed from Bede ...

called it "an execrable army, savager than any race of heathen yielding honour to neither God nor man" and that it "harried the whole province and slaughtered everywhere folk of either sex, of every age and condition, destroying, pillaging and burning the vills, churches and houses". Several doubtful stories of cannibalism were recorded by chroniclers, and these same chroniclers paint a picture of routine enslavings, as well as killings of churchmen, women and infants.

By February King Stephen marched north to deal with David. The two armies avoided each other, and Stephen was soon on the road south. In the summer David split his army into two forces, sending William fitz Duncan to march into

Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

, where he harried

Furness

Furness ( ) is a peninsula and region of Cumbria in northwestern England. Together with the Cartmel Peninsula it forms North Lonsdale, historically an exclave of Lancashire.

The Furness Peninsula, also known as Low Furness, is an area of vill ...

and

Craven. On 10 June, William fitz Duncan met a force of knights and men-at-arms. A pitched battle took place, the

battle of Clitheroe

The Battle of Clitheroe was a battle between a force of Scots and English knights and men at arms which took place on 10 June 1138 during the period of The Anarchy. The battle was fought on the southern edge of the Bowland Fells, at Clitheroe, ...

, and the English army was routed.

Battle of the Standard and Second Treaty of Durham

By later July 1138, the two Scottish armies had reunited in "St Cuthbert's land", that is, in the lands controlled by the

Bishop of Durham

The Bishop of Durham is the Anglican bishop responsible for the Diocese of Durham in the Province of York. The diocese is one of the oldest in England and its bishop is a member of the House of Lords. Paul Butler has been the Bishop of Durham ...

, on the far side of the

river Tyne

The River Tyne is a river in North East England. Its length (excluding tributaries) is . It is formed by the North Tyne and the South Tyne, which converge at Warden Rock near Hexham in Northumberland at a place dubbed 'The Meeting of the Wate ...

. Another English army had mustered to meet the Scots, this time led by

William, Earl of Aumale

William le Gros, William le Gras, William d'Aumale, William Crassus (died 20 August 1179) was Earl of York and Lord of Holderness in the English peerage and the Count of Aumale in France. He was the eldest son of Stephen, Count of Aumale, and his ...

. The victory at Clitheroe was probably what inspired David to risk battle. David's force, apparently 26,000 strong and several times larger than the English army, met the English on 22 August at Cowdon Moor near

Northallerton

Northallerton ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the Hambleton District of North Yorkshire, England. It lies in the Vale of Mowbray and at the northern end of the Vale of York. It had a population of 16,832 in the 2011 census, an increase ...

,

North Yorkshire

North Yorkshire is the largest ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county (lieutenancy area) in England, covering an area of . Around 40% of the county is covered by National parks of the United Kingdom, national parks, including most of ...

.

The

Battle of the Standard, as the encounter came to be called, was a defeat for the Scots. Afterwards, David and his surviving notables retired to Carlisle. Although the result was a defeat, it was not by any means decisive. David retained the bulk of his army and thus the power to go on the offensive again. The

siege of Wark, for instance, which had been going on since January, continued until it was captured in November. David continued to occupy

Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

as well as much of

Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land on ...

.

[Oram, ''David'', pp. 140–4.]

On 26 September

Cardinal Alberic,

Bishop of Ostia

The Roman Catholic Suburbicarian Diocese of Ostia is an ecclesiastical territory located within the Metropolitan City of Rome in Italy. It is one of the seven suburbicarian dioceses. The incumbent Bishop is cardinal Giovanni Battista Re. Since ...

, arrived at Carlisle where David had called together his kingdom's nobles, abbots and bishops. Alberic was there to investigate the controversy over the issue of the Bishop of Glasgow's allegiance or non-allegiance to the Archbishop of York. Alberic played the role of peace-broker, and David agreed to a six-week truce which excluded the siege of Wark. On 9 April David and Stephen's wife

Matilda of Boulogne

Matilda (c.1105 – 3 May 1152) was Countess of Boulogne in her own right from 1125 and Queen of England from the accession of her husband, Stephen, in 1136 until her death in 1152. She supported Stephen in his struggle for the English throne ...

(daughter of

Mary of Scotland, and so another niece of David) met each other at Durham and agreed a settlement. David's son Henry was given the earldom of Northumberland and was restored to the earldom of Huntingdon and lordship of

Doncaster

Doncaster (, ) is a city in South Yorkshire, England. Named after the River Don, it is the administrative centre of the larger City of Doncaster. It is the second largest settlement in South Yorkshire after Sheffield. Doncaster is situated in ...

; David himself was allowed to keep Carlisle and Cumberland. King Stephen was to retain possession of the strategically vital castles of

Bamburgh

Bamburgh ( ) is a village and civil parish on the coast of Northumberland, England. It had a population of 454 in 2001, decreasing to 414 at the 2011 census.

The village is notable for the nearby Bamburgh Castle, a castle which was the seat of ...

and Newcastle. This effectively fulfilled all of David's war aims.

Arrival of Matilda and the renewal of conflict

The settlement with Stephen was not set to last long. The arrival in England of the Empress Matilda gave David an opportunity to renew the conflict with Stephen. In either May or June, David travelled to the south of England and entered Matilda's company; he was present for her expected coronation at

Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, though this never took place. David was there until September, when the Empress found herself surrounded at

Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

.

This civil war, or "

the Anarchy

The Anarchy was a civil war in England and Normandy between 1138 and 1153, which resulted in a widespread breakdown in law and order. The conflict was a war of succession precipitated by the accidental death of William Adelin, the only legiti ...

" as it was later called, enabled David to strengthen his own position in northern England. While David consolidated his hold on his own and his son's newly acquired lands, he also sought to expand his influence. The castles at Newcastle and Bamburgh were again brought under his control, and he attained dominion over all of England north-west of the

river Ribble and

Pennines

The Pennines (), also known as the Pennine Chain or Pennine Hills, are a range of uplands running between three regions of Northern England: North West England on the west, North East England and Yorkshire and the Humber on the east. Commo ...

, while holding the north-east as far south as the river Tyne, on the borders of the core territory of the bishopric of Durham. While his son brought all the senior barons of Northumberland into his entourage, David rebuilt the fortress of Carlisle. Carlisle quickly replaced Roxburgh as his favoured residence. David's acquisition of the mines at

Alston on the

South Tyne

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþaz ...

enabled him to begin minting the

Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a la ...

's first silver coinage. David, meanwhile, issued charters to

Shrewsbury Abbey

The Abbey Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, Shrewsbury (commonly known as Shrewsbury Abbey) is an ancient foundation in Shrewsbury, the county town of Shropshire, England.

The Abbey was founded in 1083 as a Benedictine monastery by the No ...

in respect to their lands in

Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancashi ...

.

Bishopric of Durham and the Archbishopric of York

However, David's successes were in many ways balanced by his failures. David's greatest disappointment during this time was his inability to ensure control of the bishopric of Durham and the archbishopric of York. David had attempted to appoint his chancellor, William Comyn, to the bishopric of Durham, which had been vacant since the death of Bishop

Geoffrey Rufus

Geoffrey Rufus, also called Galfrid RufusEneas Mackenzie, Marvin Ross, An Historical, Topographical, and Descriptive View of the County Palatine of Durham', 1834 (died 1141) was a medieval Bishop of Durham and Lord Chancellor of England.

Life ...

in 1140. Between 1141 and 1143, Comyn was the ''de facto'' bishop, and had control of the bishop's castle; but he was resented by the

chapter. Despite controlling the town of Durham, David's only hope of ensuring his election and consecration was gaining the support of the Papal legate,

Henry of Blois,

Bishop of Winchester and brother of King Stephen. Despite obtaining the support of the Empress Matilda, David was unsuccessful and had given up by the time

William de St Barbara was elected to the see in 1143.

David also attempted to interfere in the succession to the archbishopric of York.

William FitzHerbert William Fitzherbert may refer to:

*Saint William of York, Archbishop of York

*William Fitzherbert (New Zealand politician) (1810–1891), New Zealand politician

* Sir William FitzHerbert, 1st Baronet (1748–1791), of Derbyshire

*William Fitzherb ...

, nephew of King Stephen, found his position undermined by the collapsing political fortune of Stephen in the north of England, and was deposed by the Pope. David used his Cistercian connections to build a bond with

Henry Murdac

Henry Murdac (died 1153) was abbot of Fountains Abbey and Archbishop of York in medieval England.

Early life

Murdac was a native of Yorkshire.Knowles ''Monastic Order'' p. 239 He was friendly with Archbishop Thurstan of York, who secured hi ...

, the new archbishop. Despite the support of

Pope Eugenius III

Pope Eugene III ( la, Eugenius III; c. 1080 – 8 July 1153), born Bernardo Pignatelli, or possibly Paganelli, called Bernardo da Pisa, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 15 February 1145 to his death in 1153. He w ...

, supporters of King Stephen and William FitzHerbert managed to prevent Henry taking up his post at York. In 1149, Henry had sought the support of David. David seized on the opportunity to bring the archdiocese under his control, and marched on the city. However, Stephen's supporters became aware of David's intentions, and informed King Stephen. Stephen therefore marched to the city and installed a new garrison. David decided not to risk such an engagement and withdrew. Richard Oram has conjectured that David's ultimate aim was to bring the whole of the ancient

kingdom of Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

into his dominion. For Oram, this event was the turning point, "the chance to radically redraw the political map of the British Isles lost forever".

Scottish Church

Innovations in the church system

It was once held that Scotland's episcopal sees and entire parochial system owed its origins to the innovations of David I. Today, scholars have moderated this view.

Ailred of Rievaulx

Aelred of Rievaulx ( la, Aelredus Riaevallensis); also Ailred, Ælred, and Æthelred; (1110 – 12 January 1167) was an English Cistercian monk, abbot of Rievaulx from 1147 until his death, and known as a writer. He is regarded by Anglicans an ...

wrote in David's eulogy that when David came to power, "he found three or four bishops in the whole Scottish kingdom

orth of the Forth and the others wavering without a pastor to the loss of both morals and property; when he died, he left nine, both of ancient bishoprics which he himself restored, and new ones which he erected". Although David moved the bishopric of

Mortlach east to his new burgh of Aberdeen, and arranged the creation of the diocese of Caithness, no other bishoprics can be safely called David's creation.

The

bishopric of Glasgow was restored rather than resurrected. David appointed his reform-minded French chaplain

John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

to the bishopric and carried out an

inquest, afterwards assigning to the bishopric all the lands of his principality, except those in the east which were already governed by the

Bishop of St Andrews

The Bishop of St. Andrews ( gd, Easbaig Chill Rìmhinn, sco, Beeshop o Saunt Andras) was the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of St Andrews in the Catholic Church and then, from 14 August 1472, as Archbishop of St Andrews ( gd, Àrd-easbaig ...

. David was at least partly responsible for forcing semi-monastic "bishoprics" like

Brechin

Brechin (; gd, Breichin) is a city and former Royal burgh in Angus, Scotland. Traditionally Brechin was described as a city because of its cathedral and its status as the seat of a pre-Reformation Roman Catholic diocese (which continues today ...

,

Dunkeld

Dunkeld (, sco, Dunkell, from gd, Dùn Chailleann, "fort of the Caledonians") is a town in Perth and Kinross, Scotland. The location of a historic cathedral, it lies on the north bank of the River Tay, opposite Birnam. Dunkeld lies close to t ...

, Mortlach (Aberdeen) and

Dunblane

Dunblane (, gd, Dùn Bhlàthain) is a small town in the council area of Stirling in central Scotland, and inside the historic boundaries of the county of Perthshire. It is a commuter town, with many residents making use of good transport links ...

to become fully episcopal and firmly integrated into a national diocesan system.

As for the development of the parochial system, David's traditional role as its creator can not be sustained. Scotland already had an ancient system of parish churches dating to the

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

, and the kind of system introduced by David's Normanising tendencies can more accurately be seen as mild refashioning, rather than creation; he made the Scottish system as a whole more like that of France and England, but he did not create it.

Ecclesiastical disputes

One of the first problems David had to deal with as king was an ecclesiastical dispute with the English church. The problem with the English church concerned the subordination of Scottish sees to the archbishops of York and/or Canterbury, an issue which since his election in 1124 had prevented

Robert of Scone

Robert of Scone (died 1159) was a 12th-century bishop of Cell Rígmonaid (or Kilrymont, now St Andrews). Robert's exact origins are unclear. He was an Augustinian canon at the Priory of St. Oswalds, at Nostell. His French name indicates a Norman ...

from being consecrated to the see of

St Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fou ...

(Cell Ríghmonaidh). It is likely that since the 11th century the bishopric of St Andrews functioned as a ''de facto'' archbishopric. The title of "Archbishop" is accorded in Scottish and Irish sources to

Bishop Giric and

Bishop Fothad II.

The problem was that this archiepiscopal status had not been cleared with the papacy, opening the way for English archbishops to claim overlordship of the whole Scottish church. The man responsible was the new aggressively assertive Archbishop of York,

Thurstan

:''This page is about Thurstan of Bayeux (1070 – 1140) who became Archbishop of York. Thurstan of Caen became the first Norman Abbot of Glastonbury in circa 1077.''

Thurstan or Turstin of Bayeux ( – 6 February 1140) was a medie ...

. His easiest target was the bishopric of Glasgow, which being south of the

river Forth

The River Forth is a major river in central Scotland, long, which drains into the North Sea on the east coast of the country. Its drainage basin covers much of Stirlingshire in Scotland's Central Belt. The Gaelic name for the upper reach of th ...

was not regarded as part of Scotland nor the jurisdiction of St Andrews. In 1125,

Pope Honorius II

Pope Honorius II (9 February 1060 – 13 February 1130), born Lamberto Scannabecchi,Levillain, pg. 731 was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 21 December 1124 to his death in 1130.

Although from a humble background, ...

wrote to John, Bishop of Glasgow ordering him to submit to the archbishopric of York. David ordered Bishop John of Glasgow to travel to the

Apostolic See

An apostolic see is an episcopal see whose foundation is attributed to one or more of the apostles of Jesus or to one of their close associates. In Catholicism the phrase, preceded by the definite article and usually capitalized, refers to the S ...

in order to secure a

pallium

The pallium (derived from the Roman ''pallium'' or ''palla'', a woolen cloak; : ''pallia'') is an ecclesiastical vestment in the Catholic Church, originally peculiar to the pope, but for many centuries bestowed by the Holy See upon metropol ...

which would elevate the

bishopric of St Andrews to an archbishopric with jurisdiction over Glasgow.

Thurstan travelled to Rome, as did the Archbishop of Canterbury,

William de Corbeil

William de Corbeil or William of Corbeil (21 November 1136) was a medieval Archbishop of Canterbury. Very little is known of William's early life or his family, except that he was born at Corbeil, south of Paris, and that he had two brothers. E ...

, and both presumably opposed David's request. David however gained the support of King Henry, and the Archbishop of York agreed to a year's postponement of the issue and to consecrate Robert of Scone without making an issue of subordination. York's claim over bishops north of the Forth were in practice abandoned for the rest of David's reign, although York maintained her more credible claims over Glasgow.

In 1151, David again requested a pallium for the Archbishop of St Andrews. Cardinal John Paparo met David at his residence of Carlisle in September 1151. Tantalisingly for David, the Cardinal was on his way to Ireland with four ''pallia'' to create four new Irish archbishoprics. When the Cardinal returned to Carlisle, David made the request. In David's plan, the new archdiocese would include all the bishoprics in David's Scottish territory, as well as

bishopric of Orkney and the

bishopric of the Isles. Unfortunately for David, the Cardinal does not appear to have brought the issue up with the papacy. In the following year the papacy dealt David another blow by creating the archbishopric of Trondheim, a new Norwegian archbishopric embracing the bishoprics of the Isles and Orkney.

Succession and death

Perhaps the greatest blow to David's plans came on 12 July 1152 when Henry, Earl of Northumberland, David's only son and heir, died. He had probably been suffering from some kind of illness for a long time. David had under a year to live, and he may have known that he was not going to be alive much longer. David quickly arranged for his grandson

Malcolm IV

Malcolm IV ( mga, Máel Coluim mac Eanric, label=Medieval Gaelic; gd, Maol Chaluim mac Eanraig), nicknamed Virgo, "the Maiden" (between 23 April and 24 May 11419 December 1165) was King of Scotland from 1153 until his death. He was the eldest ...

to be made his successor, and for his younger grandson

William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

to be made Earl of Northumberland.

Donnchad I, Mormaer of Fife

Donnchad, Earl of Fife (1113–1154), usually known in English as Duncan, was the first Gaelic magnate to have his territory regranted to him by feudal charter, by King David in 1136. Duncan, as head of the native Scottish nobility, had the jo ...

, the senior magnate in Scotland-proper, was appointed as ''rector'', or

regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

, and took the 11 year-old Malcolm around Scotland-proper on a tour to meet and gain the homage of his future Gaelic subjects. David's health began to fail seriously in the spring of 1153, and on 24 May 1153, David died in

Carlisle Castle. In his obituary in the ''

Annals of Tigernach

The ''Annals of Tigernach'' (abbr. AT, ga, Annála Tiarnaigh) are chronicles probably originating in Clonmacnoise, Ireland. The language is a mixture of Latin and Old and Middle Irish.

Many of the pre-historic entries come from the 12th-centur ...

'', he is called ''Dabíd mac Mail Colaim, rí Alban & Saxan'', "David, son of Malcolm, King of Scotland and England", a title which acknowledged the importance of the new English part of David's realm.

Veneration

David I is recognised as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church, with a feast day of 24 May, though it appears that he was never formally canonized. There are churches in Scotland which have him as their patron.

Historiography

Medieval reputation

The earliest English assessments of David I portray him as a pious king, a reformer and a civilising agent in a barbarian nation. For William of Newburgh, David was a "King not barbarous of a barbarous nation", who "wisely tempered the fierceness of his barbarous nation". William praises David for his piety, noting that, among other saintly activities, "he was frequent in washing the feet of the poor" (this can be read literally: his mother, who is now patron saint of Scotland, was widely known and lauded for the same practice). Another of David's eulogists, his former courtier

Ailred of Rievaulx

Aelred of Rievaulx ( la, Aelredus Riaevallensis); also Ailred, Ælred, and Æthelred; (1110 – 12 January 1167) was an English Cistercian monk, abbot of Rievaulx from 1147 until his death, and known as a writer. He is regarded by Anglicans an ...

, echoes Newburgh's assertions and praises David for his justice as well as his piety, commenting that David's rule of the Scots meant that "the whole barbarity of that nation was softened ... as if forgetting their natural fierceness they submitted their necks to the laws which the royal gentleness dictated".

Although avoiding stress on 12th-century Scottish "barbarity", the Lowland Scottish historians of the later Middle Ages tend to repeat the accounts of earlier chronicle tradition. Much that was written was either directly transcribed from the earlier medieval chronicles themselves or was modelled closely upon them, even in the significant works of

John of Fordun

John of Fordun (before 1360 – c. 1384) was a Scottish chronicler. It is generally stated that he was born at Fordoun, Mearns. It is certain that he was a secular priest, and that he composed his history in the latter part of the 14th cen ...

,

Andrew Wyntoun

Andrew Wyntoun, known as Andrew of Wyntoun (), was a Scottish poet, a canon and prior of Loch Leven on St Serf's Inch and, later, a canon of St. Andrews.

Andrew Wyntoun is most famous for his completion of an eight-syllabled metre entitled, '' ...

and

Walter Bower

Walter Bower (or Bowmaker; 24 December 1449) was a Scottish canon regular and abbot of Inchcolm Abbey in the Firth of Forth, who is noted as a chronicler of his era. He was born about 1385 at Haddington, East Lothian, in the Kingdom of Sc ...

. For example, Bower includes in his text the eulogy written for David by Ailred of Rievaulx. This quotation extends to over twenty pages in the modern edition, and exerted a great deal of influence over what became the traditional view of David in later works about Scottish history. Historical treatment of David developed in the writings of later Scottish historians, and the writings of men like

John Mair John Mair may refer to:

*John Major (philosopher)

John Major (or Mair; also known in Latin as ''Joannes Majoris'' and ''Haddingtonus Scotus''; 1467–1550) was a Scottish philosopher, theologian, and historian who was much admired in his day ...

,

George Buchanan

George Buchanan ( gd, Seòras Bochanan; February 1506 – 28 September 1582) was a Scottish historian and humanist scholar. According to historian Keith Brown, Buchanan was "the most profound intellectual sixteenth century Scotland produced." ...

,

Hector Boece

Hector Boece (; also spelled Boyce or Boise; 1465–1536), known in Latin as Hector Boecius or Boethius, was a Scottish philosopher and historian, and the first Principal of King's College in Aberdeen, a predecessor of the University of Abe ...

, and Bishop

John Leslie ensured that by the 18th century a picture of David as a pious, justice-loving state-builder and vigorous maintainer of Scottish independence had emerged.

Moreover, Bower stated in his eulogy that David had always an ambition to join a

crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were i ...